Advertisement

Table Of Contents

Key points

What makes a market? If there’s one thing that you can guarantee about the stock market, it’s that everyone has an opinion. At first blush, it seems fairly obvious that with so many different people participating in the market, there’s bound to be differences of opinion. What many observers and inexperienced investors/traders don’t do, however, […]

What makes a market?

If there’s one thing that you can guarantee about the stock market, it’s that everyone has an opinion. At first blush, it seems fairly obvious that with so many different people participating in the market, there’s bound to be differences of opinion.

What many observers and inexperienced investors/traders don’t do, however, is to look deeper at what it is they’re actually saying by admitting that there are so many different opinions. By acknowledging the differences of opinion in the market, the most profound insight is that not everyone can be right at the same time. In other words, somebody has to be right and somebody has to be wrong. It is this very disagreement, in fact, that makes a market.

Two’s company but three’s a market?

So why is this seemingly trivial piece of information actually incredibly valuable? To understand why, we have to take a step back and understand first where a “market” comes from.

Simply put, a market arises because a buyer wants to buy something and a seller wants to sell something. Where they have to come to some agreement on is price. It is for that reason that markets are sometimes referred to as “price discovery mechanisms”. One of the favourite questions Sparx encourages beginner traders to ask is: “how much is something worth?” Think about that for just a moment. The answer is “whatever someone is willing to pay for it”. Without both a buyer AND a seller, there is NO market.

Markets are born out of disagreement; they are built on one party believing one thing and another believing the exact opposite. For this reason, buyers and sellers compete directly with one another in what some call a “zero-sum” game meaning that the “winner” wins at the expense of the “loser”. While this is mostly true, there are also slews of “middle men” or brokers that facilitate buyers and sellers’ transactions (more on that in another article).

In bringing together buyers and sellers, “the market” performs an important function – it discovers how much something is worth. If you own a shiny piece of metal or a home and you want to find out how much it is worth you have to find out its “market value”. In other words, if you are a seller you have to know how much a buyer is willing to pay for your “thing” and this leads to a very thorny question – if nobody wants to buy what you’re trying to sell, how much is it really worth?

Markets that can give you a price for an item immediately are called “spot markets” i.e. you can sell/buy something on the spot. The other type of market price you might be interested in is how much something is worth in the future. Farmers, for example, need to know how much a crop is worth before they decide to plant it (i.e. will they make more money planting corn or soybeans?) so the prices for these items are set for a time period which gives predictability on pricing. For the moment we will focus on the stock market (which is a spot market).

One of the easiest examples of a “market” to think of is when people sell their houses. Lots of things can motivate a person to sell their house. Regardless of the reason, one of the first things a homeowner has to do is to figure out what their house is worth and what they are willing to sell it at. Most homeowners know that if the price is too high nobody will buy regardless of how “great” the owner thinks the house is (e.g. location, nearby amenities, age, condition etc.). If the price for the house is too low, the owner will have to deal with lots of interested offers but will not make as much money.

Somewhere between “too high” and “too low” is “just right” – the price that both a buyer and a seller can accept. When the number of potential buyers is high, they will likely try to outbid one another in order to obtain the item. When there are too few buyers, however, they may have a very different price that they want to pay than what a seller wants to sell at, leading to a wide difference between what people want to pay (known as a “spread”). So what is the house actually worth? Is it what the buyer wants to buy it for or is it what the seller wants to sell it for or is it the price that something similar was sold at? The term for that price is usually referred to as “Fair market value”. On a side note, it’s exactly because “fair market value” couldn’t be figured out that the global financial system was cast into such turmoil.

In the stock market, the “thing” that people are buying and selling are stocks (shares of a company also called “equities” or “securities”) and therefore the stock market should really be considered as “a market of stocks”. When thought of in this way, many of the seemingly strange occurrences of the “stock market” begin to make sense. When there are huge swings in prices of stocks, it is usually because of dramatic shifts in opinion between buyers and sellers. One of the questions you can ask when you hear about these wild swings is whether there are lots of buyers/sellers or few – the more buyers/sellers the more accurate the price will reflect supply/demand. When there are fewer participants there is greater uncertainty as to what something is worth and so prices jump around all over the place.

Most of us know a market when we see one – a local farmers market, a flea market, a supermarket or even a shopping mall. The stock market (or the market of stocks) is actually a bit misleading because it suggests there is an actual location, but in truth it is a “public entity” for the transacting of stocks. To use the example above, when people talk about the “housing market” they are not talking about a great big place where people bring homes to sell – instead it describes the overall trading activity of a particular product (in this case houses).

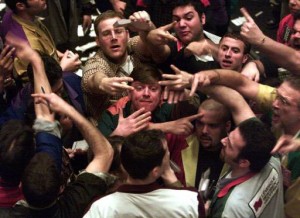

The stock market is a marketplace for equities and describes the overall buying and selling activity of stocks. “But what about Wall Street and all those pictures we see on the news of screaming traders?” you might be wondering – well the places where stocks actually get exchanged are called…wait for it…stock exchanges.

Before the world of supercomputers and the internet, people figured out it would be a good idea to create a centralized place where they could easily trade stocks with one another – the one stop shop. Without going into the history of stock exchanges , it’s mainly important to know that exchanges act as the “place” (just like a mall) where stocks can be transacted. This great little video (even though it’s old) captures how things work.

Some of the major American exchanges are the New York Stock Exchange, the American Stock Exchange and the NASDAQ (which stands for the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation – and is very tricky to fit on a business card). In Canada, the major exchanges for stocks are the Canadian Securities Exchange, Toronto Stock Exchange (formerly known as the TSE now as the TSX) and the TSX Venture Exchange. For a handy list of major world stock exchanges you can click here.

In order to participate in the buying/selling of stocks i.e. to participate in the stock market, you will have to go through a broker or intermediary of some type. If you are the do-it-yourself kind, you’ll probably go through a discount broker that will be the gateway to you connecting to the markets. We have a great section that goes through the different discount brokerages available to Canadians here.

Asking if you can participate, however, is a very different question than asking if you should and a good financial planner can help you think through the answers to both.

Going in with eyes wide open

It’s important to be informed about markets and how they work. Many well paid and intelligent people still have trouble consistently being profitable in the stock market despite their training and vast resources. There are a lot of moving parts that influence how a market works or even if it works and we will hopefully be providing more of that information in future pieces. For now it is important to say that while there is a lot to know about the markets, some very important things to think about are things that many people don’t actually talk about.

The first is that the marketplace is a place where there are winners and losers. Winners make money from the losers and the middlemen make money from both. Even though the term “market” sounds like a fairly harmless word, it is better thought of as an arena – a place where people compete.

Trading is itself a competition and the sooner you replace either trading or markets with the words competition and arena, the sooner you will start to see it as the professionals do. In fact thinking of trading like boxing is a fairly handy way to approach things. If you don’t know what you’re doing you certainly don’t want to be stepping into the ring with a pro. Even if you do know what you’re doing you may think twice if you know your opponent fights dirty. Lastly, you have to expect that if you are stepping into the ring you’re going to take a few punches – boxers aren’t afraid to take a hit, they train how to take them properly.

Because you don’t actually need anything more than money to get started trading in the market, your only ‘hope’ of a chance is to know the rules that other participants play by. People have two fists and so technically anyone can start a fight, but that doesn’t quite seem like a good enough argument to justify stepping into the ring with a professional fighter.

The “market” lures people in with the promise of profits – and yes there are profits to be made, however, those who don’t know the rules of the game are the ones who will be giving up their money to someone who knows better.

Even if you step into the ring with both eyes open, you can still get a black eye, but at least you’ll have a fighting chance.